A Brief History of Fort York

by Dr. Carl Benn

Chair, Department of History, Ryerson University The founding of urban Toronto was a military event that occurred when John Graves Simcoe ordered the construction of a garrison on the present site of Fort York in 1793. Simcoe wanted to establish a naval base at Toronto in order to control Lake Ontario because of a war scare with the United States resulting from Britain's alliance to the native people of the Ohio Country, who were engaged in a brutal conflict with the Americans to preserve their territories. In his capacity as lieutenant-governor of the British province of Upper Canada, Simcoe also moved the provincial capital to Toronto from the vulnerable border town of Niagara during that tense period. Toronto was renamed 'York,' civilian settlement followed the government, and the settlement began to grow. During those early years, Fort York played a significant role in the economic and social development of the small backwoods community.

The founding of urban Toronto was a military event that occurred when John Graves Simcoe ordered the construction of a garrison on the present site of Fort York in 1793. Simcoe wanted to establish a naval base at Toronto in order to control Lake Ontario because of a war scare with the United States resulting from Britain's alliance to the native people of the Ohio Country, who were engaged in a brutal conflict with the Americans to preserve their territories. In his capacity as lieutenant-governor of the British province of Upper Canada, Simcoe also moved the provincial capital to Toronto from the vulnerable border town of Niagara during that tense period. Toronto was renamed 'York,' civilian settlement followed the government, and the settlement began to grow. During those early years, Fort York played a significant role in the economic and social development of the small backwoods community.

|

|

Simcoe, nevertheless, did not construct the strong defences he had planned for York. Anglo-American tensions eased by 1794, and his superiors decided that the Lake Ontario squadron should be stationed in Kingston, 250 kilometres to the east. Simcoe's original log buildings deteriorated quickly. His successors built new barracks, one hundred metres east of the present site in the late 1790s for the small garrison assigned to the provincial capital. In 1800, a residence for the lieutenant-governor, 'Government House,' was built on the present fort site.

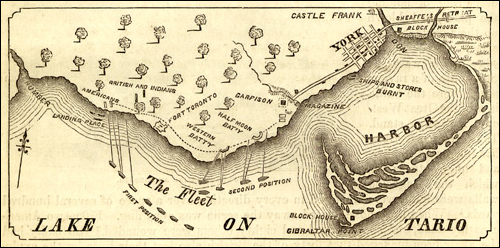

In 1807, Anglo-American relations began to deteriorate again. In anticipation of hostilities, Major-General Isaac Brock strengthened Fort York in 1811. Today's west wall and circular battery date from that time. In 1812, the United States declared war and invaded Canada. On 27 April 1813, the U.S. Army and Navy attacked York with 2700 men on fourteen ships and schooners, armed with eighty-five cannon. The defending force of 750 British, Canadians, Mississaugas, and Ojibways had twelve cannon. The Americans stormed ashore west of the fort under the cover of their naval guns. The defenders put up a strong fight, but fell back to Fort York from the landing site in the face of overwhelming odds. The British commander, Major-General Sir Roger Sheaffe, then retreated eastward and blew up the fort's gunpowder magazine (located near today's Memorial Area). The explosion was devastating: 250 Americans fell dead or wounded from its blast, including their field commander, Brigadier-General Zebulon Pike. Total losses in the six-hour battle were 157 British and 320 Americans.

The Americans stormed ashore west of the fort under the cover of their naval guns. The defenders put up a strong fight, but fell back to Fort York from the landing site in the face of overwhelming odds. The British commander, Major-General Sir Roger Sheaffe, then retreated eastward and blew up the fort's gunpowder magazine (located near today's Memorial Area). The explosion was devastating: 250 Americans fell dead or wounded from its blast, including their field commander, Brigadier-General Zebulon Pike. Total losses in the six-hour battle were 157 British and 320 Americans.

The Mississaugas and Ojibways withdrew into the forest, Sheaffe's professional troops retreated to Kingston, and the local militia surrendered the town. The Americans occupied York for six days. They looted homes, took or destroyed supplies, and burned Government House and the Parliament Buildings (near today's Front and Parliament streets). In 1814, the British retaliated when they captured Washington and burned the White House, Capitol, and other public buildings.

The Americans returned to a defenceless York in July 1813 to burn barracks and other buildings that they missed in April. Shortly afterwards, the British rebuilt Fort York on what is both today's and Simcoe's original site. In August 1814, Fort York was strong enough to repel the U.S. squadron when it again tried to enter Toronto Bay. In February 1815, word reached York that the War of 1812 had ended the previous December. It was good news: peace had returned, and the defence of Canada against American invasion had been successful.

The British continued to garrison Fort York after the war, although most soldiers moved to new barracks one kilometre west of the fort in 1841. (The officers' barracks of that 'New Fort' or 'Stanley Barracks' survives today.) During times of peace, Fort York's defences were allowed to deteriorate, only to be strengthened in periods of crisis, such as the Rebellion Crisis of 1837–41, or when war with the United States seemed imminent, such as in 1861–62.

In 1870, the Canadian government assumed responsibility for most of the country's defences, including Fort York. Canadian troops maintained the harbour defences at the fort until its guns and earthworks became obsolete in the 1880s. The army, however, did not abandon the site at that time, but used it for training, barracks, offices, and storage until the 1930s. Some military activity even took place at Fort York during World War II. Between 1932 and 1934, the City of Toronto restored Fort York to celebrate the centennial of the incorporation of the city in 1834. On Victoria Day 1934, Fort York opened as a historic site museum. Today, its defensive walls surround Canada's largest collection of original War of 1812 buildings. Even the older part of the one reconstructed building on the site, the Blue Barracks, contains a

Between 1932 and 1934, the City of Toronto restored Fort York to celebrate the centennial of the incorporation of the city in 1834. On Victoria Day 1934, Fort York opened as a historic site museum. Today, its defensive walls surround Canada's largest collection of original War of 1812 buildings. Even the older part of the one reconstructed building on the site, the Blue Barracks, contains a  significant amount of 1814-period material and is an interesting example of the efforts made during the Great Depression to create employment by restoring and rebuilding historic sites. The grounds of the fort and the surrounding land encompass part of the 1813 battlefield, remnants of Toronto's late eighteenth-century landscape, and at least two military cemeteries. Below the soil of the fort lies a vast archaeological resource, capable of significantly expanding our understanding of life in the earliest years of Toronto's settlement.

significant amount of 1814-period material and is an interesting example of the efforts made during the Great Depression to create employment by restoring and rebuilding historic sites. The grounds of the fort and the surrounding land encompass part of the 1813 battlefield, remnants of Toronto's late eighteenth-century landscape, and at least two military cemeteries. Below the soil of the fort lies a vast archaeological resource, capable of significantly expanding our understanding of life in the earliest years of Toronto's settlement.

Today, the City of Toronto, supported by The Friends of Fort York and other members of the community, operates Fort York as a historic site museum. The fort houses various exhibits, such as restored period rooms and traditional museum galleries, as well as other displays that explore the story of Ontario's turbulent military past. Staff and volunteers engage in the essential tasks common to operating any such institution of significant importance: enhancing the collection through acquiring artefacts, conserving the collection for the benefit of future generations, developing the site to meet the public's interests in the past, studying Fort York's history through archival, material culture, and archaeological research, and sharing that history through public programmes, tours, and special events.